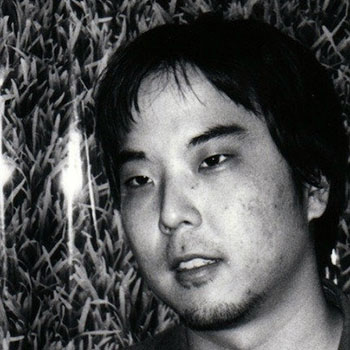

Chicago-born Chris Nazuka started spinning and producing deep house just as a second wave of loft parties and the very first wave of raves began to bubble up in Chicago and Detroit.

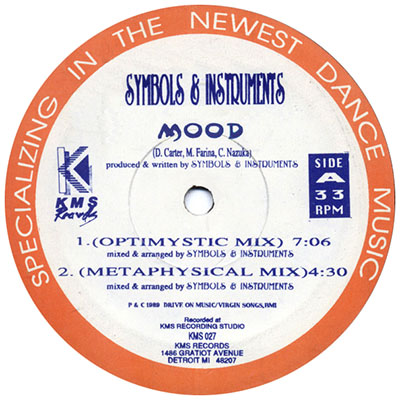

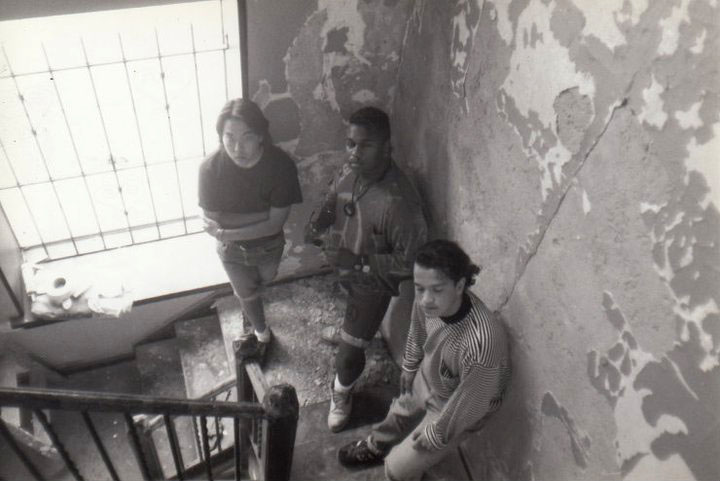

As Symbols & Instruments, Nazuka and his friends Derrick Carter and Mark Farina released the EP “Mood” on legendary Detroit label KMS in 1989. The trio lived together in a loft in Chicago’s River West neighborhood, which they called Red Nail based on their phone number. In the early 1990s all three spun at loft parties on Milwaukee Avenue in Wicker Park.

During this period, Nazuka and Carter collaborated on a series of records under their own names and as Red Nail, Shock Therapy, The Magi, and Us. Many of the releases were for Carter’s label Blue Cucaracha. Nazuka and Carter also worked with Ron Trent and Chez Damier on the classic single “Never.”

More recently, Nazuka produced the EP Night Music for Vizual, which beautifully combines new and retro sounds, beats and melodies. I spoke with him in October 2015 while researching an article for Boiler Room on connections between Chicago and Detroit’s rave scenes, illuminating the blurred lines between house and techno.

Arnold: When did you start DJing?

Nazuka: For fun, when I was in college, so ’87 or ’88 was when I got my turntables. I DJed through college, threw parties at University of Wisconsin Madison. I was friends with Mark Farina from eighth grade through high school.

I DJed through college and met Derrick [Carter] through Mark in ’88, my freshman year in college. Derrick already had a record out, and he was working at this record store called Importes [Etc.], which was one of the only big record stores at the time. It was in the Printer’s Row area. It was the store for house at the time. Gramaphone wasn’t a house record store yet, it was more like just a record store. Importes was the place where everybody got their records, and Derrick was one of the buyers there. He would call all of the distributors and get all of the new stuff.

Mark had met him, and then I met him through Mark, and we all got along, started hanging out, became friends. That’s how we first did our first record together on KMS. Derrick had already done a record for that label [as 24-7-365]. That was Kevin Saunderson’s label, who at the time was Inner City. He had just blown up, so he got all of this money and started a label. We went up there and recorded “Mood.” [We] went up there probably three or four times to do that EP.

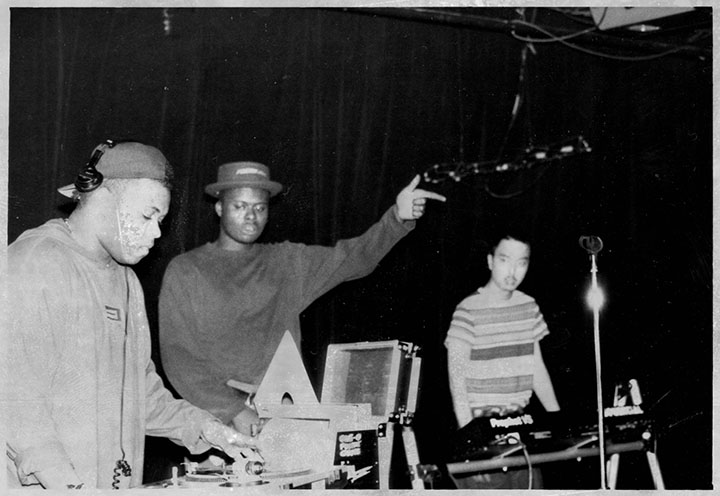

The first time we went up there, we worked in Kevin’s studio. It was right where Derrick May lived. He had his studio upstairs, and then Juan Atkins had a studio downstairs. It was all in the same building complex.

We did one of the records on that EP in Juan Atkin’s studio, the B-side, called “Tear Drops of Yesterday.” And then the other one we did in Kevin’s and then finished in this bigger studio in Detroit. That was my first record out ever. We were still nineteen years old, and we were all pretty excited about it. We did it in ’89, but I don’t think it came out until ’90. It wasn’t that big here, but overseas it did pretty well. It got attention over in England.

Had you had any musical training?

Oh yeah, I already played keyboards. I played piano and played trumpet. Me and Mark were in the band together in high school. I had a little musical background. Derrick had more of a production background. Me and Mark had been in bands in high school, New Wave bands with keyboards, so we already had the interest. And then we got into house—we were more into New Wave industrial stuff at first, me and Mark, anyway. There was that era where it crossed over. Some of the New Wave stuff was also being played in the mixes in Chicago, the hot mixes over the radio, like Anne Clark and Liaisons Dangereuses, tracks like that. European stuff was being played over here on the Chicago hot mixes. Then we really started getting into house and started buying house records.

Mark met Derrick [Carter], and I met Derrick and we all hung out. We did that first record. It did pretty well, actually. It made a couple of charts. [The] Face magazine, it made their top 100 for that year when it came out. KMS was a small label at the time.

Do you remember who came up with the name Symbols & Instruments?

I think Mark did. He came up with the name, and we all liked it, so we went with it. That’s when we met Chez Damier, because he worked with KMS at the time. He did A&R for them, and he was also an artist. He had records out, too. Eventually, he moved to Chicago and started Prescription with Cajual and stuff. We knew him from Detroit, and then he moved back to Chicago, and we started hanging out with him.

You were going to school in Madison and then you came back to Chicago?

Yeah, I graduated in ‘91, and then I came back here. Mark and Derrick were still here, so we all decided to get a place. We got this loft over by River West area, restaurant row on Randolph Street, and that was Red Nail, the name we gave it, because that was our phone number.

Did you guys build your own studios there?

Yeah, it was like a 1000-square foot loft, it was empty space, and we had to build our own drywalls. We built four rooms. Derrick had his turntables in his room, Mark had his turntables in his room, and then I had mine in my room, but we also set up the studio in my room. We had gear that we had gotten from years. We had real drum machines. It was total analog, it was way before computers and stuff. We had 909s and 808s. We had to do all of our mixes live. It was just off the fly.

It was a loft building that was pretty empty, so we could be as loud as we wanted. It was good for that time. It was easy to make music and those guys would be mixing and making tapes. Back in the day, DJs sold their mixes at the store.

Did you bounce ideas off of each other?

Yeah, totally. Mark and I did that first record together, and then Derrick and I started doing a lot more remixes. Mark didn’t do as much with us then, because at that point, he started going to California a lot, and eventually he moved to San Francisco. Then we had this other guy move into our loft, Josh Michaels, who is pretty big, Joshua Iz, Iz & Diz. When he moved here, he knew Derrick through the record store, too. We met him, all got along. He was into the same kind of stuff as we were, so he took Mark’s space. So we were there probably ‘91 until ‘95-ish.

Were you spinning at loft parties around the same time?

The Substance parties [thrown by David Gandy and Andrew Substance at 321 N Jefferson St], for me, were the original parties, because that’s when I was still in college, so it was ’89, maybe. That was before the rave thing happened, but then the loft parties on Milwaukee probably happened after ’91, because I know I was already out of school. Probably between ’91 and ’95, 6. The Milwaukee parties, I remember, were pretty big.

That was before Wicker Park looks like it does now, so you could get away with it. Kids could throw parties all night and the cops wouldn’t really hassle you, because they didn’t really care. I guess that transitioned into the rave scene, eventually, but the loft parties were a lot more intimate. For me they were a lot funner.

I guess raves were happening. The first rave I remember was the one that Wade [Randolph Hampton] threw in Chicago. It was called Life. For me, that was the first big rave that I remember. It was held in this roller rink called Rainbo, and they had the Hardkiss brothers and John Digweed, I think, was here, and then Mark and Derrick spun it. That was the first big one, and then after that other people started throwing raves around the city. And then the mayor tried to crack down on that whole scene.

Do you think the line between house and techno was more blurred at that time?

Yeah, for sure. It was whatever was good. It wasn’t like people were saying, Oh, this is techno and this is house. People would play Derrick May records mixed to house records. It wasn’t like you had to be one or the other. If it was good, it was just played, and no one really cared about the labels. Most people didn’t even know what techno was at that time. Detroit had to put out a compilation calling it techno for people to be like, Oh, this is what Detroit techno is. I definitely think back then it was a lot more blurry. I think it was better, actually, because there was less labels.

Were you guys influenced by Detroit artists?

Oh yeah, for sure. When we went out, that was one of the best parts of that KMS record. To us, those guys were our idols, especially Derrick May, Juan Atkins. And Kevin, too, for sure. Derrick [Carter] had already met him once because he’d done one record with that label, but when we went up there, me and Mark, it was our first time to meet Derrick May, and he was totally down to earth and really, really cool—just giving us good advice, and then he’d play us stuff that wasn’t released. We were freaking out, because we were just heads at that time, really into whatever was the newest thing, and I remember he had tracks on his answering machine that he would never release, and we would just call it just to hear it, because they were so dope.

And they had this club back there in Detroit called the Music Institute, and when we went up there to record, we went up there and heard Derrick May spin there. That was one of the coolest clubs I’d ever been to. To this day, it was still one of the coolest, ’cause it was really raw and it was huge, but they had a massive sound system—speakers piled on top of each other fifteen feet in the air.

I remember “French Kiss,” it had just first come out, and Derrick May was playing that, just beating it, and we were nineteen, just totally influenced by those guys and just into it. So Detroit definitely was a big influence, because it was different than what was happening musically here.

Did Chicago music get harder and faster around that time, too?

Oh yeah, for sure. I think what eventually became the Relief-type stuff was definitely influenced by techno. Ron Trent “Altered States” was a huge cut at Importes to bridge that techno and Chicago sound. He ended up working with Chez and those two started Prescription, which was a whole other mix of Detroit and Chicago.

It seems like you and Derrick Carter were really prolific ’94, ’95.

We did a lot of remixes. It wasn’t about money, because we didn’t really make any money doing it [laughs]. It was more about getting our name out there and just having fun. There were a lot of labels that were just starting up in Chicago. Like Large Records had just started, so we did a couple of remixes for them. Then we did a Dajae remix. Yeah, we just did a lot of remixes. And eventually Derrick started this label called Blue Cucaracha. That was a chance for us to put stuff out of our own under different names.

Most of the stuff we did was for smaller, obviously independent labels. It was before social media, so you just had to know somebody or just hooked up somehow. Like we did this record for this label called Bomb Records, David Alvarado’s label. That was because his label was distributed by John Acquaviva which was the same guy that was distributing Blue Cucaracha. It was cool, because it was a little community of people that were into the same type of things. That’s how we did remixes for other people. We liked their stuff, so they’d be like, Hey you want to do a remix? Like, Yeah, sure.

Did you make things for your own use, just to play out?

Oh yeah, totally. The cool thing was there was a weekly that Derrick did at a place called Foxy’s [at W Belmont Ave and N Halsted St]. It was this tiny club that you could fit maybe a hundred people on the dance floor, max. It was a great little bar. It was a Tuesday night that he did, so anyone that would go there was people that were into it. Nobody really goes out on a Tuesday unless you’re into the music. We would make stuff at our loft, and he could play it that night to see how people liked it. It was just a great way to get instant feedback about how a track does or how it sounds on the dance floor.

It sounds like an environment that really sparked your creativity.

For sure. A lot of people walked through that loft. I remember before Cajmere started Cajual, he would come there and hang out and play us some of the stuff he was working on. Wade, whenever he was in town, he stayed with us. Fast Eddie and K-Alexi lived across the street.

And there was the second Warehouse club right on Randolph was there. It was a cool area, because it wasn’t really gentrified yet, so it was still pretty raw, but it was close to Shelter and the clubs. It was fun.

I think that era was pretty influential. It was the second generation of house music. A lot of big artists now got their start there. It was a lot more of an innocent area, because it was just kids doing what they liked. It was a little more pure than it is now. There’s so many labels. So many people say they’re DJs. I think anybody can be a DJ now in this era. Back then you really had to prove yourself. If you weren’t good, you’re not going to get called.

In that era, there’s only a few underground Chicago DJs that were for the kids. That was Mark [Farina] and Derrick [Carter] and Diz [Dwayne Washington], Spencer [Kincy, aka Gemini]. Those were the DJs that the kids going to parties, at least in Chicago, knew about. You could always count on them. If one of them were spinning at a party, you could at least count on it being pretty good.

When the rave scene took over, it changed a little bit. I think the music was kind of different than it was at the loft parties.

How so?

It started getting a little trancey. Less soulful and more drugged out. It seems like it splintered more. People would really specialize in one sound and the crowd would follow them. Back then, you didn’t think of it as this is techno and then this is house. For me it was all house. Ultimately for me a good DJ is someone who can just play good music and it doesn’t have to be tied down by a brand.

If you were there, you’ll remember it. It was a lot of fun parties that kids were throwing themselves. It wasn’t sponsored by any liquor company or anything like that. They were just kids throwing parties themselves. They were all illegal, and they had to worry about getting busted, but it was worth it.