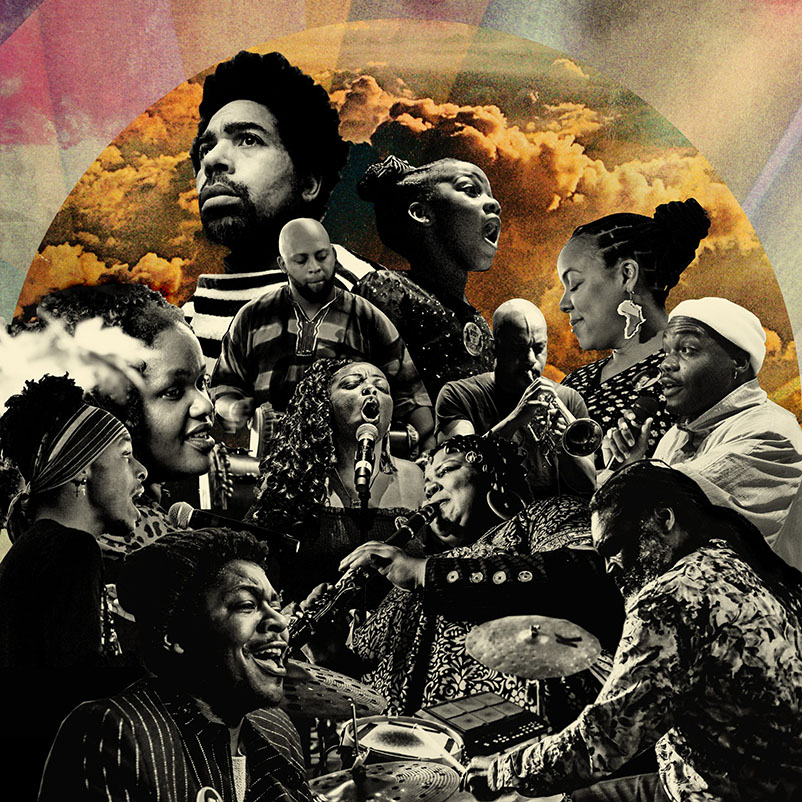

Damon Locks’ Black Monument Ensemble offers a unique sensory experience. The group’s live performances, often comprised of over a dozen artists, combine choral singing, recorded samples, live instruments, costume, and dance to form a beautiful, immersive whole.

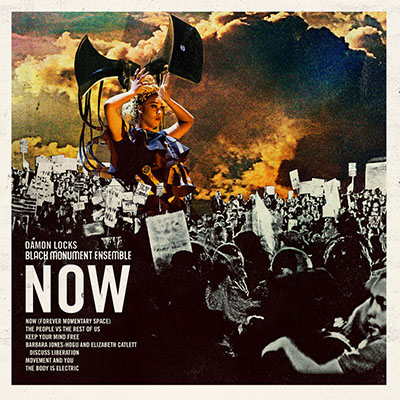

In March 2021, during one of the pandemic lock-downs, I interviewed Locks by phone about his second Black Monument Ensemble album, NOW. Parts of that conversation informed a short feature for Chicago Magazine. Here for the first time is a full version of the Q&A, which touches on Locks’ inspiration, process, and wider artistic practices.

Locks grew up in Silver Spring, Maryland where he became involved in D.C.’s punk music scene. In the late 1980s, he attended the School of Visual Arts in New York for a couple of years before transferring to The School of the Art Institute of Chicago. In 1988, he started the band Trenchmouth, which went on to release four albums and several singles. Locks then co-founded The Eternals, which is still active. He began Black Monument Ensemble, originally as a solo project, in 2015.

Arnold: What was the origin of Black Monument Ensemble?

Locks: Well, the idea of this kind of thing was always in my head. I was always inspired to create or have a group that felt like it connected to the world around us. When I was a kid, Public Enemy would put out an album, and then they’d be on the news. Not only was it attractive to people that liked hip-hop, but it was also something that affected regular life. And the themes they had in their songs, like “By the Time I Get to Arizona,” and things like that, I was inspired by that, how the songs reverberated out into life.

I think that thematically the work that was done in Trenchmouth or The Eternals, all addressed issues ’round real life and the world. They were artistically, physically engaged material, but it was always in a music scene. When I started to work in prison–I teach art in prison through a program called Prison + Neighborhood Arts/Education Project–when I started that in 2014, I just was really inspired to make stronger connections–to make music that had a variety of access points, where people could just hear it.

The work in prison was about getting voices heard through artwork that you never hear from. I was also less concerned with making sure that the people in the music scenes hear music than just everyone. I had this idea that I wanted to figure out how I could access people in different places, because I felt like people knew what to expect from shows.

When I was a little kid, shows were dynamic and exciting and amazing. When I would see Bad Brains or Nation of Ulysses or Sun Ra Arkestra, you would go, “Oh my God, I’ve never seen this before!” but by 2010, you knew what was going to happen at a show. So I was thinking what if something else happened. So I really had to workshop that for a long time.

But also Mike Brown was getting murdered, and people were getting murdered very publicly. It really caused me to think about what I needed to do, and how would I respond to this culture that felt very much like we were on our way to a world where people’s civil rights were getting revoked left and right.

I had to really contemplate on how I’d respond to it, and I didn’t know if it was going to be visual art or music, but I decided I would have to figure out how to do it using sound, so I started out using electronics, and I was doing this at the same time as being in The Eternals and the Exploding Star Orchestra [with Rob Mazurek].

So I started doing these solo electronic performances [in 2015] based around themes, culling from Civil Rights era recordings and playing these recordings, first on records, literally, and making beds of sound so people could hear, whether it’s Angela Davis or Ruby Dee and Ossie Davis reciting Langston Hughes. I was presenting these words that were addressing many of the same issues that we’re still facing today, so that people could hear them anew.

I started doing this as a process. I was doing it at art shows, I was doing it in people’s living rooms, I was doing it in people’s basements, I was doing it in galleries, just trying to figure this out.

Over the course of a couple of years, I had this idea that I wanted to bring almost a choir together, because I had been listening to a lot of gospel music that was the soundtrack to Civil Rights. I had this idea that I could write music that was physically engaged using Black voice. I also started working with Move Me Soul on projects, who are a dance company on the West Side from the Austin neighborhood. Once I started getting the voices together, I really looked forward to the idea of bringing dance and the voice and expanding the group, ’cause originally the group was me and a percussionist, named Damien Thompson, and the electronics. I knew always that I wanted to expand the group to more drums and another melodic instrument.

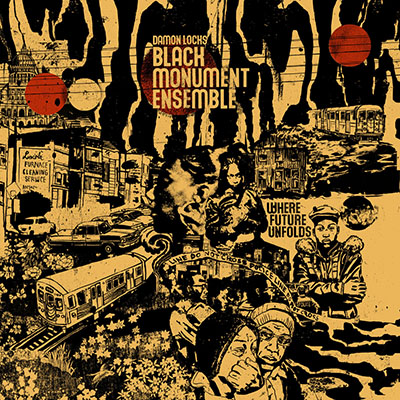

Where Future Unfolds [2019] was the culmination. All of those ideas that happened that night, which was the album, is the first night that we were able to bring all of the elements together and perform them in one fell swoop.

How much does live performance factor into the project, and what aspects of that appeal to you?

Well, live performance is really where it’s at. I think that the [South Shore] Cultural Center show was good, but out of all the shows that could be documented front to back, that one was OK. We weren’t in charge of the lighting. It was kind of dark. But the spirit was there. I think that the Garfield Park Conservatory and the Chicago Cultural Center downtown, oh, just stunning!

If I have a scenario where we can have a beautiful environment, and the full seventeen or so people can be performing, to me, that’s the jam, because then people really have to think about what’s happening. It’s dance and it’s music, and you’re like, is this theater, is this a band? What is happening? And it lives in a space, like I took time to imagine what Phil Cohran’s shows would have been like, or an Arkestra show in the ’60s might have been like, or even Eddie Gale’s Black Rhythm Happening, what their shows might have been like. And maybe they were something like this.

I feel like when we get to perform in all of the full scenarios, that’s the real experience, but it doesn’t negate the recorded experience. It’s just much more powerful live.

Have you been suffering from withdrawal with the pandemic?

For sure. Of course I miss performing, yes, but I miss the community of playing music. Not only do I miss working on songs with Black Monument Ensemble, but I miss working on songs with The Eternals. I’ve been working on something with Rob Mazurek where I’m just sending audio files, back and forth with him. I’ve done online performances, and they can be cool, but at the end of the day, you turn off your computer and you’re already home. There’s none of the talking for two hours with people who saw the performance or people that you were performing with. So that whole community aspect is the part that I really miss.

Tell me about the process of recording NOW.

That was super challenging and really beautiful at the same time. Because when the pandemic hit, we released a song called “Stay Beautiful,” which was an outtake from the first record. It wasn’t taken out because we didn’t love it, but it was taken out just time-wise, for the length of the album. It really was apropo to release this song called “Stay Beautiful” right at the beginning of the pandemic. It was really a moving thing to do, and I think it was received really well.

Someone made a beautiful video. There was a drone video of a guy with a bicycle. The shot started right above his head, and he started bicycling around in circles as the drone pulls back, and “Black Lives Matter” was written on the ground to “Stay Beautiful.” I was just like, Wow, this is really, really amazing.

So after George Floyd and Breonna [Taylor] and Ahmaud Arbery, after the uprisings, Instagram told me that people were really turning to Where Future Unfolds as a source of solace and inspiration. People were playing it a lot, and people were listening to it anew. It inspired me to wonder what Black Monument could say contemporarily. I was really happy that Where Future Unfolds resonated, but most of the lyrics were written two years ago. The challenge of writing something in this time period seemed overwhelming, but also something that I really wanted to do.

I felt like from a lot of the people that I spoke to in the group, that they were eager to offer something new. I didn’t know what we were going to make, but I put my mind to trying to figure out what a new chapter could look like, or at least a new statement could look like.

Once it started to form into something, once it looked like some songs were going to happen, I was like how do I create a recording where there’s five vocalists and someone playing a wind instrument in the era where brass is super dangerous [due to COVID]. How do I make that happen. So I called up ESS [Experimental Sound Studio] and said, Hey, can we record in your back garden? And Alex Inglizian was like, Yeah, we could do that. And so we booked days at the end of August, and I decided to split the group in half. So we met up with Angel [Bat Dawid] and six vocalists and myself and recorded the vocals to the drum machines and samples, and then a month later, had Dana [Hall], Arif [Smith], and Ben LaMar [Gay] come and put their parts on top of it.

It was such a challenge because I wanted everyone to be safe for this project. I didn’t want to record some songs and get anyone sick. But to record these songs in this way was so different than the past, because in the past you would have a rehearsal, you’d present the music, you rehearse it, and you’d play it, and then there’d be a show and you’d play it a couple of times and then ultimately you would then record it.

I think one song was written and performed before the pandemic, and then I sent demos of the other things and I know that they got together to work on “NOW (Forever Momentary Space)” the day before the session. But almost everything was done in that moment, in the time that we were there. We had to discuss what the song was about and what the emotion of the theme would be, and we had to figure out how everything was going to happen in the sessions then and then record it.

One of the things that I’m interested in with this recording is that the first record was a document of this particular event. It was a night that there was a performance, and there was electricity in the air, and we captured that, and that became the record. So I was really interested in capturing the moment of the pandemic. And the electricity of the nervousness, that desire to be in community with each other and to offer something new that everyone was willing to put themselves out there in order to create something new, and I feel like the cicadas and the talking afterwards and the people’s excitement, all of these things, it became a new moment. There was no audience, but the day is just as important in this recording as it was for the first record, to me.

Were the performances largely improvised?

No, there was a structure to all of the songs. Some of the things that the vocalists did were created on the spot, before we recorded, and we just needed to go there. In my writing, for example, when I wrote the song “Keep Your Mind Free,” I wrote two verses, then I have a verse that I just knew the [sings falsetto], “Keep your mind free, keep your,” so I was like, this is the part. Now you guys can do whatever you want in that section, but this is the idea. And so we spent fifteen, twenty minutes, and then we got the thing that they did, which was, “Keep, keep, your, your, mind,” and they just made it into this psychedelic vocal thing that happened. I knew they would, but I had to give the framework for it so that they could then build on it.

You mentioned sharing demos. What does your compositional process look like. Do you usually record? Do you notate sheet music, too?

Mostly I just record it. I record out ideas, and then listen back to them, and then record them again. It doesn’t have to be recorded well, I just need to listen to it and see how it feels. There’s a bunch of stuff that didn’t make it to the record, because I kept listening to it, and it just didn’t come together in a way. One of the interesting things is that I didn’t have a timeline in mind when I was working on this, so a bunch of ideas existed, and then two months down the road, if I was still listening to that idea and still thought it was great, then it could still become a song. So I had to put it through its maturation by myself in my apartment, just by listening to it over and over and over again.

So when I demoed it for them, I did my best to record the song with me bringing the drum machines and samples and the singing, and then sent that to folks. And I feel pretty sure, you asked if there was improvisation, I know that Dana and Arif listened to the recordings and came to the sessions with their ideas. But I feel probably that Angel responded in real time over the course of our takes. I might have said something like, Well you should stop there, or you should bring that thing back in here, but I feel like she developed a bunch of her stuff, and I know that Ben did the same thing on the melodica or cornet when he was in the studio.

The phrase “Forever Momentary Space” evokes capturing something that’s elusive, something that just happens in that improvisational moment. A lot of your work seems to deal with time. Is there something that fascinates you about that concept?

Yeah, I think so. There’s something about being able to look at the past and the present to know more about the future, or imagine the future so that you can know more about the present. For me, all of these times are smashed together and always have been. There’s something about my visual work, say my digital collages or even some of my other work, drawn work, might have contemporary imagery in it that looks like it’s from several decades ago. I’m a big fan of science fiction, so it’s always been this big compression of the future and the present and the past, anyway.

When I use voices from the past in sound bites or samples, I don’t think of them as old. They’re saying something that’s just as valid right this moment as it ever has been. There’s this stream of thought happening. There’s a wonderful sample by Mattie Humphries that says, “Time is just the difference between knowing now and knowing nothing. Because if you know now fully, it’s past, present, and future.” She said that, and I was just like, Wow, she pulled my thoughts out of my head and said it. And she also said it in the ’60s [laughs].

Your work seems very tied to Chicago jazz history. Is there something specific about the sound and community here that drew you to it?

Well, I came here for art, and I had to really get to know the city. But I’ve been here since 1988, so I’m going to say this is my city. And I think what has been an early inspiration was to learn about the history of Chicago and know that people like Curtis Mayfield or Mahalia Jackson were walking the same street that I’m walking. That was pretty impressive and daunting.

But to eventually be able to connect in some ways to this large history that Chicago has musically, if I could offer something to that or be in conversation with that, or be a part of that history in any way, that would be a huge honor and be very gratifying, because organizations like the AACM or artistic movements and collectives like AfriCOBRA, have a really big influence on me as a person and as a person making stuff out in the world. To know that there’s a rich history of that here in Chicago and know that it’s really not so far removed. There are people around that make themselves available to you and you can connect with, and you can talk to on the phone. I think that that’s really inspiring.

Chicago is a big influence. It’s given me opportunity to connect to a lot of musicians but also connect to a lot of activists and educators, academics, dancers, poets. There’s a huge community of people that have been super active for years, honing their craft, and when this world came to a grinding halt, we found out that art isn’t extraneous, it’s absolutely necessary.